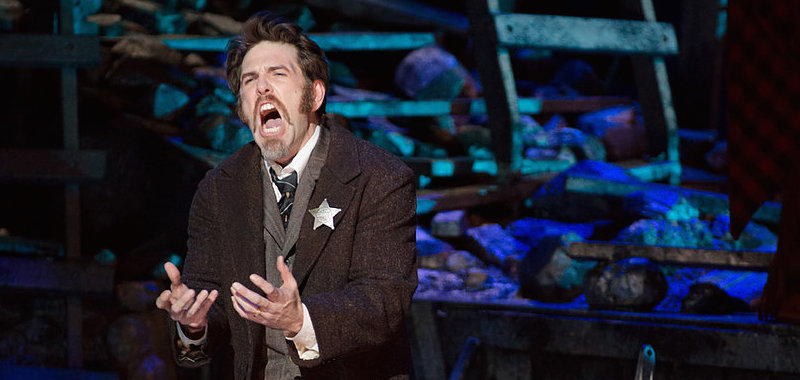

Opera in the Modern Age: A Conversation with Michael Mayes, Baritone

Baritone Michael Mayes has engaged audiences throughout the United States and beyond with his vocal and theatrical talents. Both a proponent of contemporary opera and lover of traditional opera, Mr. Mayes has a rich and versatile resume of roles. In the 2017-2018 season alone, Mr. Mayes will have performed Joseph De Rocher in Dead Man Walking with Teatro Real in Madrid and the Barbican in London, REV23 with Beth Morrison Projects, Doug in Everest with Lyric Opera of Kansas City, Starbuck in Moby Dick with Pittsburgh Opera, Sweeney Todd with Atlanta Opera, and Conte di Luna in Il trovatore with Central City Opera. We had the pleasure of sitting down with Mr. Mayes and discussing his musical background, his performance career, and his views on the future of opera.

Modern Singer: Much of your work is in the realm of contemporary opera. What do you find most rewarding about working on more modern pieces?

Michael Mayes: The subject matter, the cultural and social issues that operas are currently attacking, have such a therapeutic and beneficial effect for the singers on stage. For me, the ultimate goal is to be a part of the rolling tide of artistic development in my art form. You can do this by updating older pieces, but I find that those artistic impulses are better served in a piece that’s contemporary. When an audience views a contemporary piece, it is often much easier for them to connect with the artistic message. If I sing an English piece about combat-induced PTSD, that is a subject that touches all of us. You have an automatic resonance with everyone in that audience. And you’re singing in English, so there’s no delay between when you say something and when the audience comprehends it. That immediate access to the material is one of the greatest aspects of performing contemporary work.

MS: Do modern themes and subjects in contemporary opera make it easier for you to personally connect to these pieces?

MM: In a larger sense, those themes are what allowed me to connect to opera as an art form. I didn’t grow up with opera; I grew up with country and bluegrass and rock’n’roll, so it was always difficult for me to connect with traditional operas. With contemporary American opera, the subject matter has a resonance with me, the language is what I’m familiar with, and the musical language often has a lot of basis in American musical idioms. That’s what allowed me to relate to the art form as a whole. It wasn’t until I did contemporary American opera that I understood the feeling behind the more traditional pieces. It took me understanding how to communicate complex emotional and psychological concepts through opera in English before I could actually communicate them in Italian, German, and French.

MS: You mentioned that you grew up with genres like country and rock’n’roll. How do those genres affect the way you approach your job as an opera singer?

MM: I don’t see a lot of difference between those styles of music and opera. The scope and scale are different, but the general idea of a three-and-a-half minute song is the same as a three-and-a-half hour opera; opera is just a longer form. I actually do a country music show called “From Opera to Opry: Liquor, Love, and the Lord,” which is a show I wrote with some friends of mine. The first half is all opera, and you’ll see an aria from Tosca, an aria form Don Giovanni, a duet, etc. In the second half, those opera singers come back in costume as their alter egos, Cletus McHatfield and the McHatfield Family Singers, and they perform country music. Every piece on the first half has an analog to a piece in the second half, becoming a conversation about the universality of music. So for me, the styles are not that different. The reason why opera means so much to me is that I can communicate and resonate with an audience in the same way that I can communicate with an audience through country and bluegrass music.

It’s the same with contemporary and traditional opera. Whether I’m singing De Rocher or Rigoletto, I want them both to have the same emotional intensity and the same immediacy of access to emotion. As an opera singer, you spend a lot of time translating from one language to another. But if you really think about what we do for a living, we translate emotion into sound. You’re just trying to find the best way to communicate that emotion through your sound.

MS: Where do you see contemporary opera fitting amongst the more established operas in major opera houses and companies?

MM: If you look back at the past ten or fifteen years, there’s been a crazy explosion of what we call “opera with a conscience:” operas that take on really complex social issues. I think that’s the future of opera. In order for us to really connect with new audiences, you have to hit that nexus between artistic expression and social activism. The American tapestry is so rich, so diverse, with so many stories that are dying to be told, and opera is the best storytelling medium there is. These operas that deal with complex social issues are not culminations of the issues, they’re the beginning of conversations about the issues. People ask me questions about Dead Man Walking, about what kind of statement it’s trying to make. Dead Man Walking isn’t trying to make a statement; there’s not a position in the piece. It’s not an anti-death-penalty piece. The point of the piece isn’t to tell you that you’re right or wrong, it’s to make you ask a question. This is a conversation the opera started, a conversation that continues once people get out of their chairs and go home. I think the future of opera is not entertainment, but service. Contemporary pieces are serving their communities by asking these relevant questions.

MS: If you were to have a contemporary opera commissioned, what might you want to sing?

MM: I have two answers. First of all, I would love to sing Daniel Plainview from There Will Be Blood, which is based on the Upton Sinclair novel, Oil! It’s a fantastic story, and I’ve been dying for someone to set that.

On a different note, I think the explosion of gun violence in this country would be a perfect subject for opera to cover, specifically in regards to the relationship between the police and the African American community. I think that’s a subject long overdue for an operatic treatment because opera has this way of transcending time and barriers in a way that finds a back door into peoples’ psyches. Right now we are so polarized in our country, but music and opera bring people from all different backgrounds and viewpoints together and allows them to experience a group catharsis. When you experience a catharsis with somebody, it’s hard to hate them.

For me, opera is a cure. We are in an incredibly dynamic time; things are changing every day. And while it may be unsettling or scary to live in this world, there’s no better time to be an artist than right now. As we move forward, I want us to reach out and bring young composers up, these musicians that are wrapping current culture into classical music, and give them all the resources they need to become the next great American composers. The future of opera is in the future, not in the past.

You can see Michael Mayes in his role debut as Sweeney Todd at Atlanta Opera, running from June 9 - 17 at the Cobb Energy Performing Arts Centre. You can also see him this summer as Count di Luna in Central City Opera’s Il Trovatore, running from July 14 - August 3.